What are Neuronal Ceroid Lipofuscinoses (NCLs)?

Commonly referred to as Batten disease, the Neuronal Ceroid Lipofuscinoses (NCLs) denote several different genetic life-limiting neurodegenerative diseases that share similar features. Although the disease was initially recognised in 1903 by Dr Frederik Batten, it wasn’t until 1995 that the first genes causing NCL were identified. Since then over 400 mutations in 13 different genes have been described that cause the various forms of NCL disease.

What causes NCL?

Our cells contain thousands of genes that are lined up along chromosomes. Human cells contain 23 pairs of chromosomes (46 in total). Most genes control the manufacture of at least one protein. These proteins have different functions and include enzymes which act to speed up molecular chemical reactions. The NCLs are caused by abnormal genes, which are unable to produce the required proteins. As a result, the cells do not work properly and this leads to the development of symptoms associated with these diseases.

How are NCLs inherited?

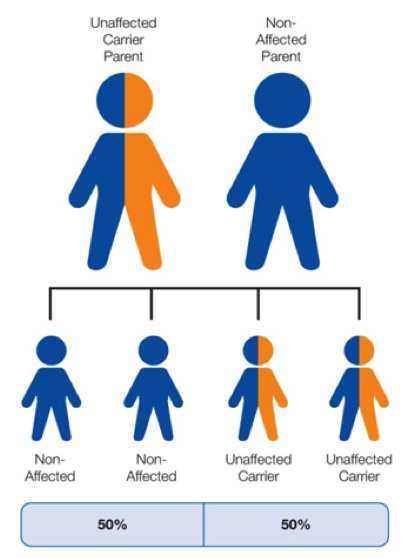

Most forms of NCL are inherited as “autosomal recessive” disorders. This is one of several ways that a trait, disorder, or disease can be passed down through families. An autosomal recessive disorder means that both copies of the gene are abnormal (one from each parent) with neither working properly. Therefore the disease does not depend on the sex of an individual and both biological parents, of a child with this diagnosis, will be carriers of the disease but physically unaffected by it.

What are the chances of inheriting an NCL?

A child born to parents, who both carry the autosomal recessive mutation in the relevant gene, has a 25% (1 in 4) chance of inheriting the abnormal malfunctioning genes from both parents and developing a form of Batten disease. They will have a 50% (1 in 2) chance of inheriting one abnormal gene, which would make them a carrier who is unaffected by the disease. There is a 25% (1 in 4) chance of the child being born with two normal genes and therefore being non-affected (not a carrier).

When it is known that both parents are carriers of the abnormal gene, we refer to there being a 2 in 3 chance of a child being a carrier, once it is established that they are unaffected by the disease.

With any pregnancy, the probability of a child inheriting one or both genes from their parents is the same each time, irrespective of any sibling’s status.

How common is it?

We estimate that approximately 1 – 3 children are diagnosed with an infantile form of the disease each year, meaning there are probably between 15 and 30 affected children in the UK.

We estimate that approximately 7 – 10 children are diagnosed with a late-infantile (including variants) form of the disease each year, meaning there are probably between 30 and 60 affected children and young people in the UK.

We estimate that approximately 3 – 4 children are diagnosed with a juvenile form of the disease each year, meaning there are probably between 30 – 40 affected children and young people in the UK. Adult NCL is extremely rare, although affected families have been identified in several different countries.

Therefore in summary, we estimate that there are approximately 100 – 150 children, young people and adults currently living with an NCL diagnosis in the UK.

What are the symptoms and how does the disease progress?

There are various differences in terms of the progression of each genetic variant; however a number of shared symptoms will inevitably occur in each individual’s journey with the disease. These include an increasing visual impairment resulting in blindness; complex epilepsy with severe seizures that are difficult to control; myoclonic (rapid involuntary muscle spasm) jerks of limbs; difficulties sleeping; the decline of speech, language and swallowing skills; and a deterioration of fine and gross motor skills that result in the loss of mobility. Ultimately the child or young person will become totally dependent on families and carers for all of their needs. Other symptoms that are commonly seen are hallucinations, memory loss and challenging behaviours. Death is inevitable and, depending on the age of onset and specific genetic diagnosis, may occur anywhere between early childhood and young adulthood.

Are there any treatments?

Currently there is no cure for any form of the disease and therefore specialist symptom management and therapy is essential to assist in maintaining a good quality of life for children and their families. Holistic support for parents, siblings and wider family members is extremely important throughout their journey. For the CLN2 variant only there is a treatment which has demonstrated an ability to delay aspects of physical decline and there are more details on our CLN2 for Brineura page.

What research is being done?

Although there are limited funds available, research into possible methods for slowing the progression of the disease and potentially curative treatments are on-going. These are taking place in the UK and across the globe. For more information, please see the research section of our website or contact: admin@bdfa-uk.org.uk

What are the genetic considerations?

After learning that a child or young person has a form of NCL some families will have younger siblings who may be affected but have not displayed any symptoms. It may also be possible that older unaffected siblings are carriers of the disease and may want to understand how this may affect their family choices when they are older.

When only one parent is a carrier of the abnormal gene, and the other is non-affected, there is a 50% (1 in 2) chance that any child will be an unaffected carrier.

If parents are considering having additional children, they can access specialist advice and support from their local clinical genetics service following a referral from their GP. Prenatal testing may be possible in the early stages of any future pregnancy

What are the practical implications for families?

As the illness progresses, specialist equipment and aids will become necessary. Items are likely to include specialist seating, buggies/wheelchairs, supportive aids and equipment for visual impairment, bathing and toileting aids, hoisting equipment and a specialist bed/mattress.

It is likely that changes will be needed in the home environment to enable the family to appropriately care for an individual with the disease. These may include installing ramps, widening doorways and providing suitable floor surfaces. A purpose-built wet room with a specialist bath or shower is commonly needed and there are various other aspects that will require consideration.

Education will continue to be important for the family though there will be many aspects that require consideration and significant assistance from various professionals. Specialist support and possibly schools or colleges will often play a role at some point in each individual’s journey. (For more specific information or assistance please contact BDFA Support support@bdfa-uk.org.uk)

Significant financial challenges are likely to present themselves for most families, especially as the disease progresses. Many parents find they have to take on a full-time caring role, which understandably can add to the economic strain as well as having an emotional and practical impact upon their lives.

For more information, please click here for the support section of our website or contact the BDFA Family Support Team: support@bdfa-uk.org.uk or 0800 046 9832